Could This Conclave Elect the Church’s Second African Pope?

In recent centuries, the papacy has slowly but surely begun to reflect the global nature of the Catholic Church. In 1978, the world saw the election of Pope John Paul II, a Pole whose papacy broke a long series of Italian popes and brought a new nationality to the Vatican. After him came Pope Benedict XVI of Germany and then Pope Francis of Argentina, the first pope from South America to assume the role. Now, many eyes are turning toward Africa, a continent that has become a vibrant heart of Catholic faith and evangelization, but has not provided the Church its pontiff since the election of Pope Victor, a native of Roman Africa (Modern-day Tunisia), in 189 A.D.

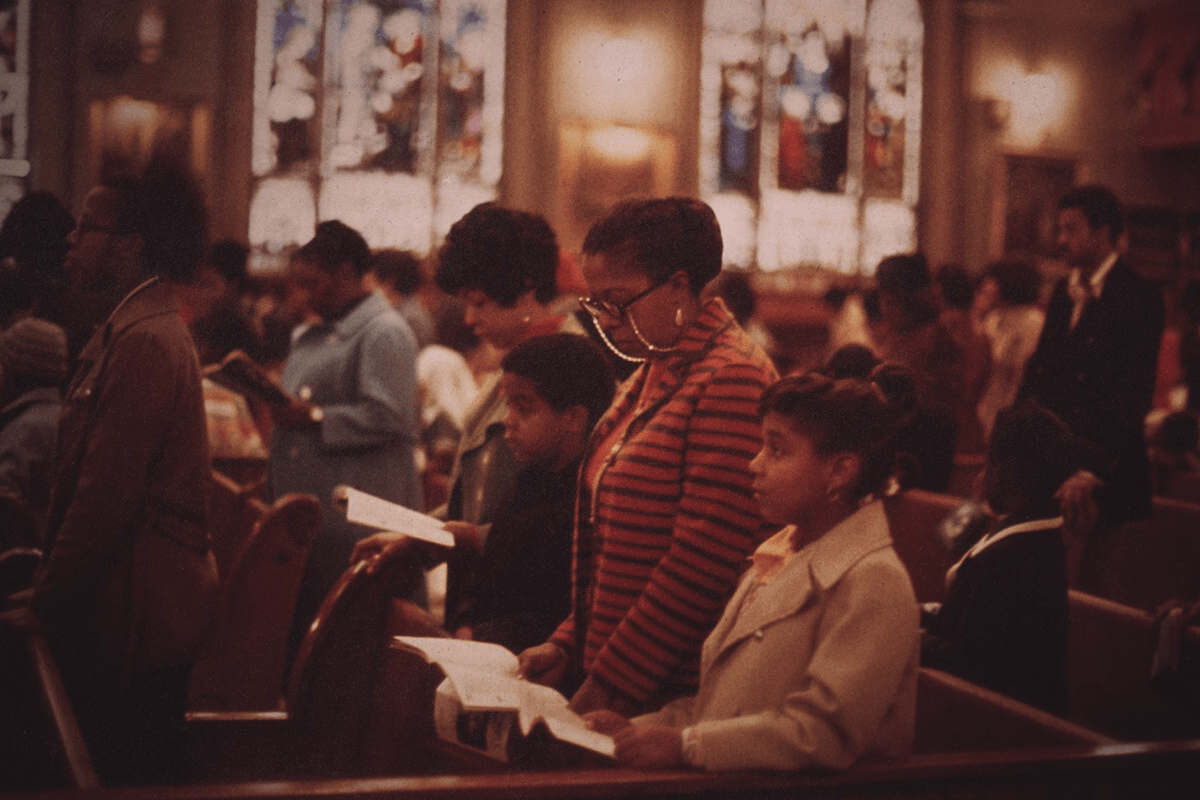

Africa is often described as the “periphery” of the Catholic Church. It is a region far from the institutional and theological epicenters in Rome and around Europe. Yet, the Church in Africa is anything but peripheral in spirit or numbers. The Catholic population in Africa has swelled, and its influence is becoming impossible to ignore. The numbers tell a compelling story: in Nigeria, a staggering 79% of Catholics attend Mass weekly, according to a recent World Values Survey. This is the highest rate of any country surveyed. By contrast, Lebanon follows at 69%, while the United States trails far behind at only 24%. The vibrancy of African Catholicism is evident not just in attendance, but in vocations, community engagement, and religious fervor, even in the face of adversity.

The growth of the Church in Africa has often come hand-in-hand with immense suffering. In regions plagued by conflict, poverty, and religious persecution, African Catholics have demonstrated remarkable resilience. Nigeria stands out not only for its sheer number of believers but also for its many martyrs. Terrorist groups such as Boko Haram have targeted Christian communities, and yet the faith of those communities remains unshaken. This combination of suffering and devotion has given rise to a theology rooted in hope, endurance, and witness, qualities that resonate deeply with the Gospel.

In this context, the idea of an African pope is not merely a symbolic gesture of inclusion, it is a potential re-centering of the Church’s priorities and imagination. For decades, African clergy have been playing increasingly prominent roles within the global Church.

Cardinal Peter Turkson of Ghana is widely respected for his leadership on issues of social justice and environmental responsibility. He served as the first head of the Vatican’s Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, where he championed Catholic responses to poverty, migration, and inequality. His articulate moral vision and deep commitment to the Church’s social teaching have made him a standout figure in the global hierarchy.

Another key contender could be Cardinal Robert Sarah of Guinea. Known for his theological depth and spiritual discipline, Sarah has held several important positions within the Roman Curia, including Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. Sarah’s positions reflect a strong adherence to tradition and liturgical reverence. He has a large following among clergy and laity who advocate for a more contemplative, prayerful Church. His African heritage, combined with a rigorous intellectual formation and deep spirituality, makes him a compelling figure in any discussion of the papacy.

The election of an African pope would also be a powerful fulfillment of Pope Francis’ consistent call to listen to the margins, or the “peripheries,” as he often called them. Pope Francis emphasized the importance of seeing the Church not only through the lens of Europe but through the eyes of those who suffer, who struggle, and who live on the geographic and existential frontiers. What better embodiment of this vision than a pope from Africa, where the faith is lived daily in its rawest and most authentic forms?

Moreover, a pope from Africa could reframe global Catholicism for the 21st century. An African pope could serve as a bridge between North and South, tradition and innovation, suffering and hope. Of course, the conclave is guided not by polling data or regional quotas but by prayer, discernment, and the mystical promptings of the Holy Spirit. Cardinals are instructed to look for a leader who embodies pastoral wisdom, theological depth, and a heart aligned with Christ.

Even then, it would be naïve to think geography plays no role. The Church is global, and so too is its leadership. Whether or not this conclave results in the election of an African pope, the very fact that such a possibility is being seriously considered is significant. It is a testament to the undeniable contributions of African Catholics to the universal Church. The seeds of faith planted by missionaries centuries ago have blossomed into a robust and dynamic Church in Africa, one that may soon find itself at the very center of Catholic leadership.